Of Gods, Books and Poetry

A conversation between Jude Cowan Montague and Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún

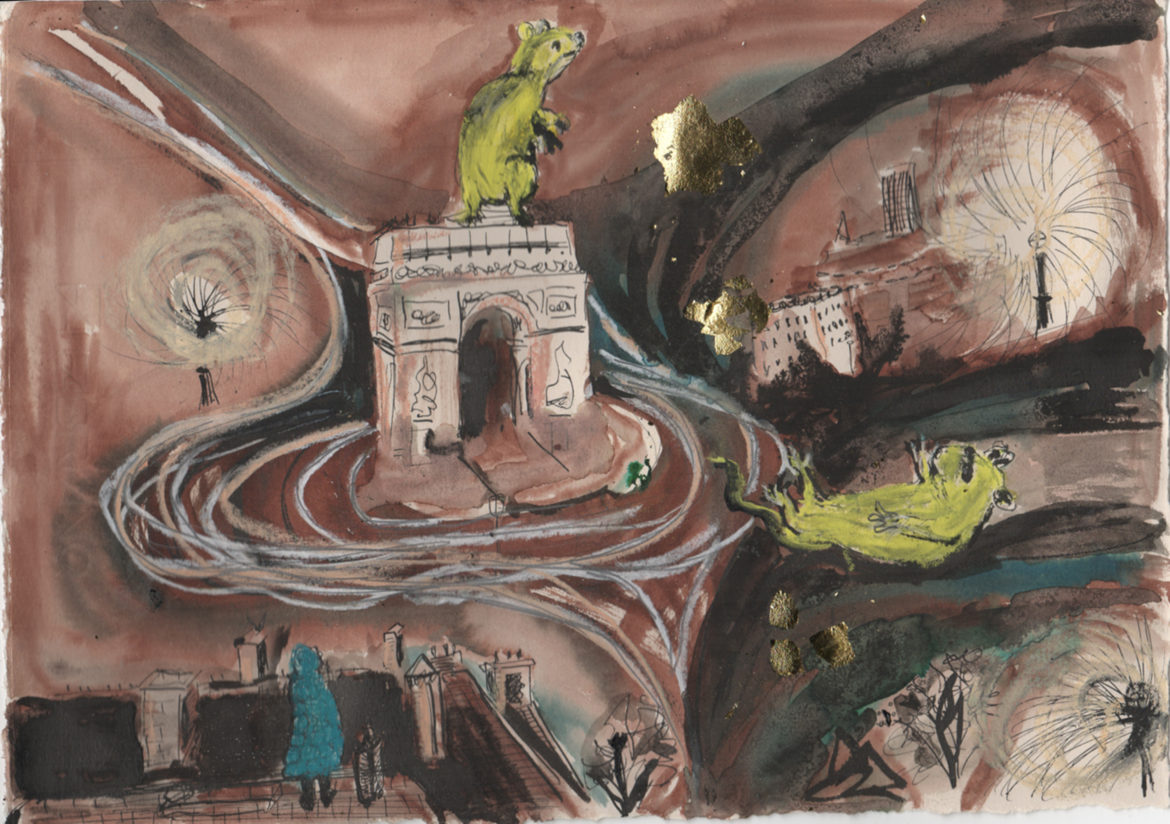

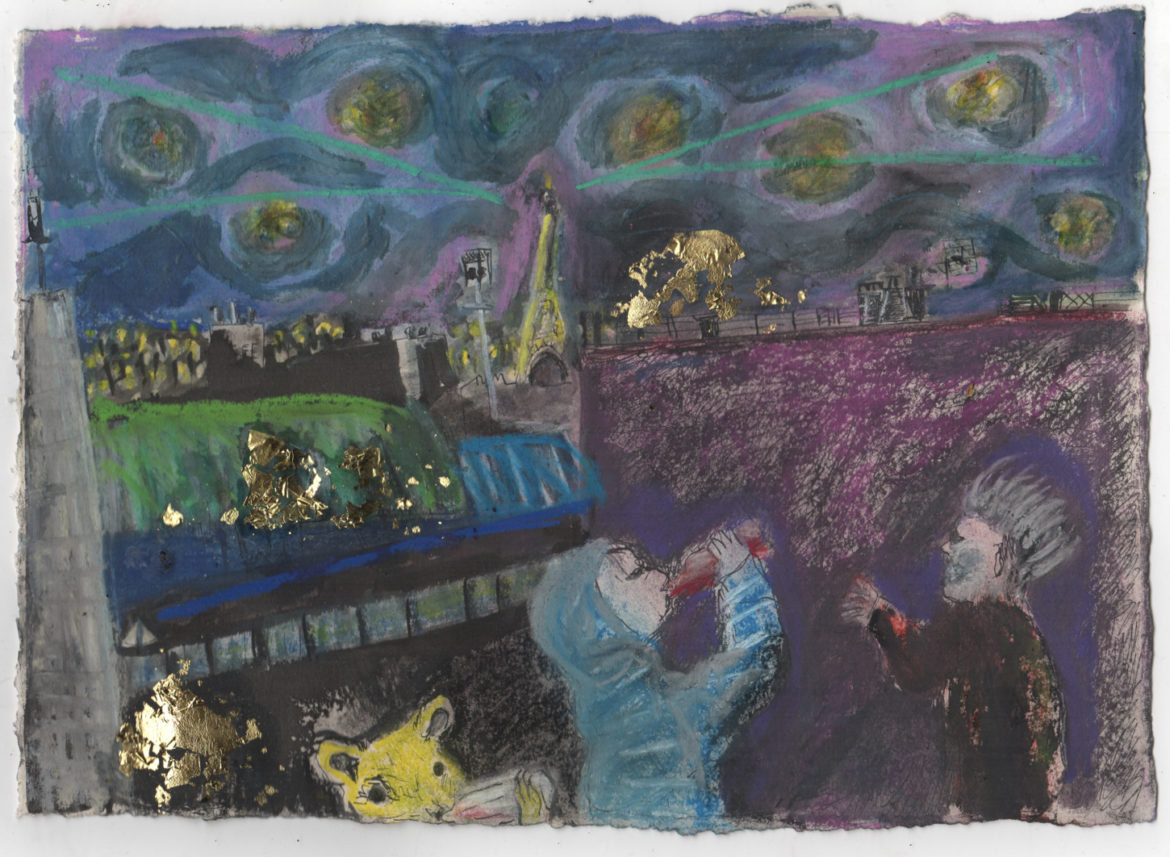

Introit: Kola Tunbosun met Jude for the first time in October 2018—at Pembroke College, Oxford, to be precise—where he had gone to present his debut collection of poetry, Edwardsville by Heart. A few days later, they met again in London at Resonance FM, to discuss his book, art, music, and a number of other issues. It was a fascinating conversation. But a few points from that conversation have remained with them over the distance, he back in Lagos, Nigeria after the book tour, and Jude now on an art exhibition for her series of paintings titled Paris Pavements. They caught up for a third time, via email, to flesh out what drew them to each other, and what convergences exist in their work, in her art, and their outlook on the world. Below is the result of that conversation.

Kola Tunbosun: You seem fascinated by this story of Èṣù I told you during our chat on The News Agents, and about his journey through traditional lore into modern-day life of technology and the internet. Do you know why the story resonates with you this way?

Jude Cowan Montague: After talking to you I have a vivid image in my head of him as a character. My image, perhaps unsurprisingly, reminds me of my father. He also was a man who tried to set up situations which compelled people into arguments or to make decisions. It’s hard to describe without giving an example, but my dad was quite theatrical and would push people into situations where they had to make a decision. He took delight in flouting social conventions, in pushing people to flout social conventions. I feel very affectionate to my dad and I feel very affectionate towards Èṣù. I don’t want either to be classified as the devil!

KT: It is very theatrical, this characteristic. Something that every society seems to need to interrogate its own assumptions. Is your father typically Irish or was he an aberration among his peers?

JCM: He was Scottish but lived in Ireland. People called him a character but I think in his generation there were others a bit like him judging from some stories people tell of their own fathers when they hear one of my poems, let me share one to illustrate him a little.

Mile End

Picking up the receiver, putting it down,

picking it up again. In the glass booth

that separates the user of the telephone

from the street, the woman was clearly nervous,

as I would be, stuck with multiple offerings of SEX

on pink and black stickers, peeling.

Personally, I fiddle with coins,

reluctant to touch the cigarette-burnt metal

because of the mere idea of germs.

I’m sure she was waiting for a call back,

as he tapped on the glass. And tapped again.

Don’t worry, I said. Let’s move on.

He pulled the door loudly, in best northern.

It doesn’t work like that love. You have to put money in!

KT: I like that poem!

JCM: Do the stories of Èṣù remind you of any real life incidents or individuals?

KT: Very many, from my childhood days to modern times. What I’ve found interesting — and I think it’s why the Christian missionaries gravitated towards this idea of Èṣù as ‘the devil’ — is that what results from one’s encounter with it is determined either by one’s own attitude or outlook or the conditions present in the moment. When the outcome is negative, we blame it on the ‘evil’ character that push us to do them rather than on how we ourselves have fallen for its trap.

My father, I would say, was one of those characters. I’ve relayed this story, many times, about the time he came to my school and pretended like he didn’t speak English so as to force my classmates (we were all about eight years old at the time) to respond to him in Yorùbá. I was terribly embarrassed by the incident, but it has remained for me one of the most memorable beginnings of my engagement with language advocacy. It was also him, as I described, who “made” me give myself a tribal mark because I was determined to prove him wrong on a subject that fascinated me at the time. You can still see the lone mark on my face. But in the end, it was my decision, and I learnt something from it.

How much of your father do you think influenced what you have become today?

JCM: The adult I am is very directly related to my father. Through rebelling and questioning his instructions as well as following his advice. Ironically he told me to question everything. He was a fan of ‘clear thinking’ and understanding the rhetoric of advertising. I remember one classic Pelican he encouraged me to read. Looking it up online I’m thrilled by the bold graphic cover and design. It says, there are mysteries, look for them. Don’t be content with the surface message. It’s almost a religious design, perhaps because it references the idea of the third eye.

There were many literary books, novels, plays and poems, that made him a man of ideas, and reading them after him helped form my own philosophy. Favourites of his would include Bernard Shaw, Sheridan and Boswell’s. Interestingly, Samuel Johnson seems to have been a man of provocative statements as well. Some of which feel very appropriate here.

‘The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.’ ‘Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel,’ one quote that feels very relevant to me in times of Brexit, and presumably described some awful behaviour and attitudes in eighteenth-century imperialist England. One that a lot of people would agree with in these capitalist heady days, but not me, is ‘No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.’

We met at Samuel Johnson’s old Oxford college, Pembroke, where you were reading from your first published collection of poems Edwardsville by Heart. It felt a significant connection at the moment itself, standing there by his writing desk beneath an oil painting of the dictionary man, and somehow I am not surprised we are still talking about him. I remarked on the connection between you two, both, in very different environments, advocates of literacy, literature, and well used written and spoken language.

Of course, it’s easy to talk about these well-read English texts. What about literary works in Yorùbá that I should read? Are there any in translation you’d recommend, possibly featuring Èṣù or other gods? I’m fascinated by folklore, fairy tale, religious stories that forge morality or take us on imaginative journeys beyond realistic everyday activities and environments.

KT: There are two ways to approach Yorùbá mythology. There is the classic ‘literature’ which is the sacred Ifá corpus, which is mostly oral, but which scholars have tried to document in print over the years. There are scattered references all around the place, mostly by Wándé Abímbọ́lá or Ifáyẹmí Ẹlẹ́búìbọn. The latter also did a couple of record albums with the stories which, unfortunately, you can only appreciate as rhythm because it is not translated. Here’s one. Then there are quasi-modern literary texts, notably by D.O. Fágúnwà who wrote fantasy, mixing traditional myths with his own invented forms, featuring interesting forest characters. Wọlé Ṣóyínká translated his most prominent book into English, with the title Forest of a Thousand Daemons.

I have been fascinated by Johnson over the years, but I had no idea his connection to Pembroke until that evening, and I was glad to participate in his aura around the room and write on his desk. I have also bought that book you recommended and I hope to learn a bit about his life from Boswell’s eyes. And speaking of language, yesterday was Noam Chomsky’s 80th birthday. Another modern-day sage for his work in language. I am also fascinated by the little trivia that Johnson did not complete his degree, yet his work and influence surround us now, enough for the university to memorialize him this way. We have many people in Nigeria as well whose work, primarily in translating the bible and documenting Yorùbá inadvertently helped the survival of the language into this age. There was Samuel Àjàyí Crowther, the most prominent of those early translators, Ayọ̀ Bámgbóṣé who spearheaded the creation of the modern Yorùbá orthography, and another Samuel Johnson, a Yorùbá man, who wrote The History of the Yorùbás, an important book. Their legacy follows me around and influences my work.

JCM: Some fascinating linguistic coincidences happening here.

I have started to research Èṣù via the grand old modern encyclopaedia, Wikipedia, which tells me that he has travelled around the world, very appropriate for a god who is associated with paths, journeys and messaging. Perhaps his influence is being felt right now in this conversation. He is playing with our sense of identity and language by throwing these coincidences into the conversation so we can explore new connections and think about ideas.

KT: Is there any part of old Western (Scottish or Irish) mythology that has survived in your own imagination or work?

JCM: Quite fitting here would be to mention the poet, novelist and essayist James Hogg, also known as the Ettrick Shepherd. He used Scottish mythologies, fairy tales and supernatural stories to help create the most incredibly profuse body of work. His image as a self-taught shepherd-poet no doubt helped him establish himself as a literary figure but for me, he’s a real genius of a storyteller. His most famous work is The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner’ in which the Calvinist doctrine of pre-ordained salvation leads the protagonist deeper into a psychological pit of his own making. In Hogg’s fiction, the devil is in the religion. It’s delightfully macabre and is an utterly compelling read. It also summons up the landscape of Scotland for me, the short days and the dark, dark nights.

He also writes wonderful pieces on witches and their exciting transformations. The shape-shifters, turning into birds, battling in the sky above the windy moors.

Of course, Robert Burns is such an important songwriter as well as a poet and I have to commend him as one of the few respected Romantic poets whose verse has lent itself easily to varied song settings. For me, he’s essential because of that link with the folk song but I do find his hymns to various lassies a little tedious, to say the least. Some of his poems make me feel so strongly how the #metoo backlash against white male literary domination was inevitable and long overdue.

The Irish side of my family I more married into but the poet John Montague is my daughter’s great-uncle. She has the name Blánaid who was the lover of the hero Cú Chulainn, and there are different, very vivid versions of how she uses her intelligence to help her lover defeat her captor, the warrior Cú Roí. She is cast as a magic-maker herself, spinning spells to aid her chosen side, but as is often the case with women in such narratives of war, she ends up a victim of the conflict.

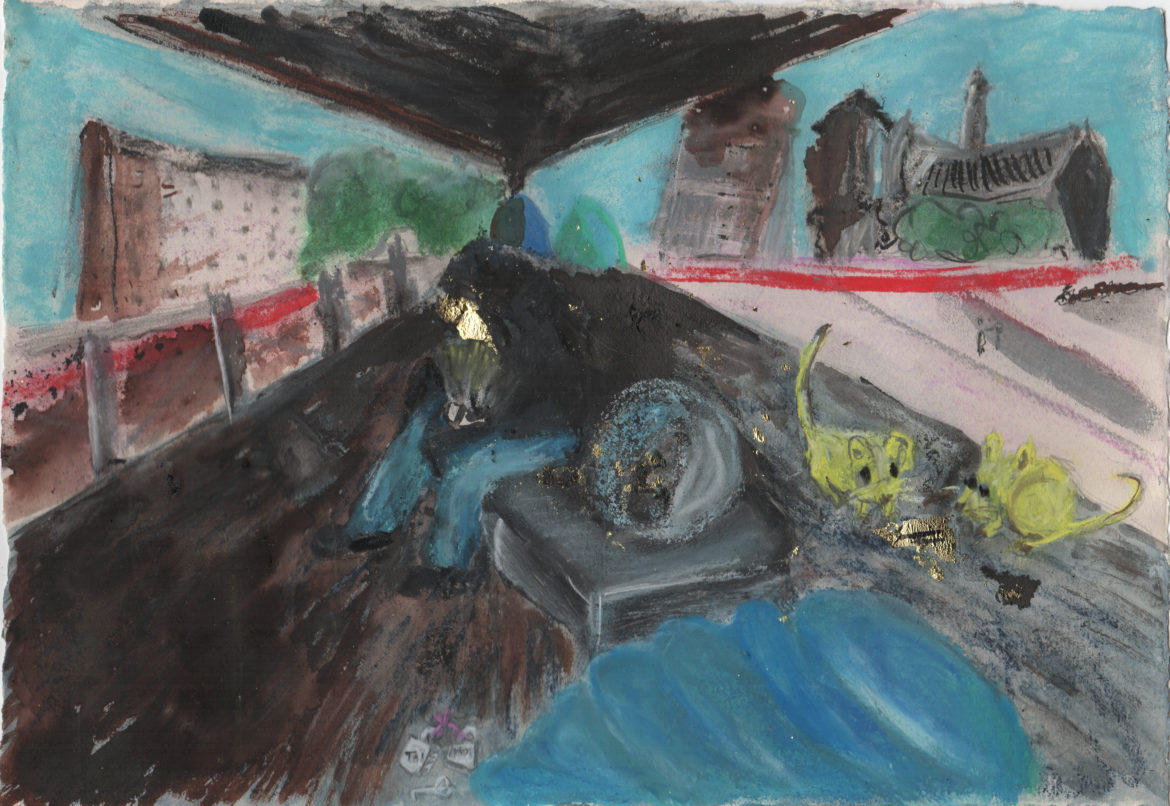

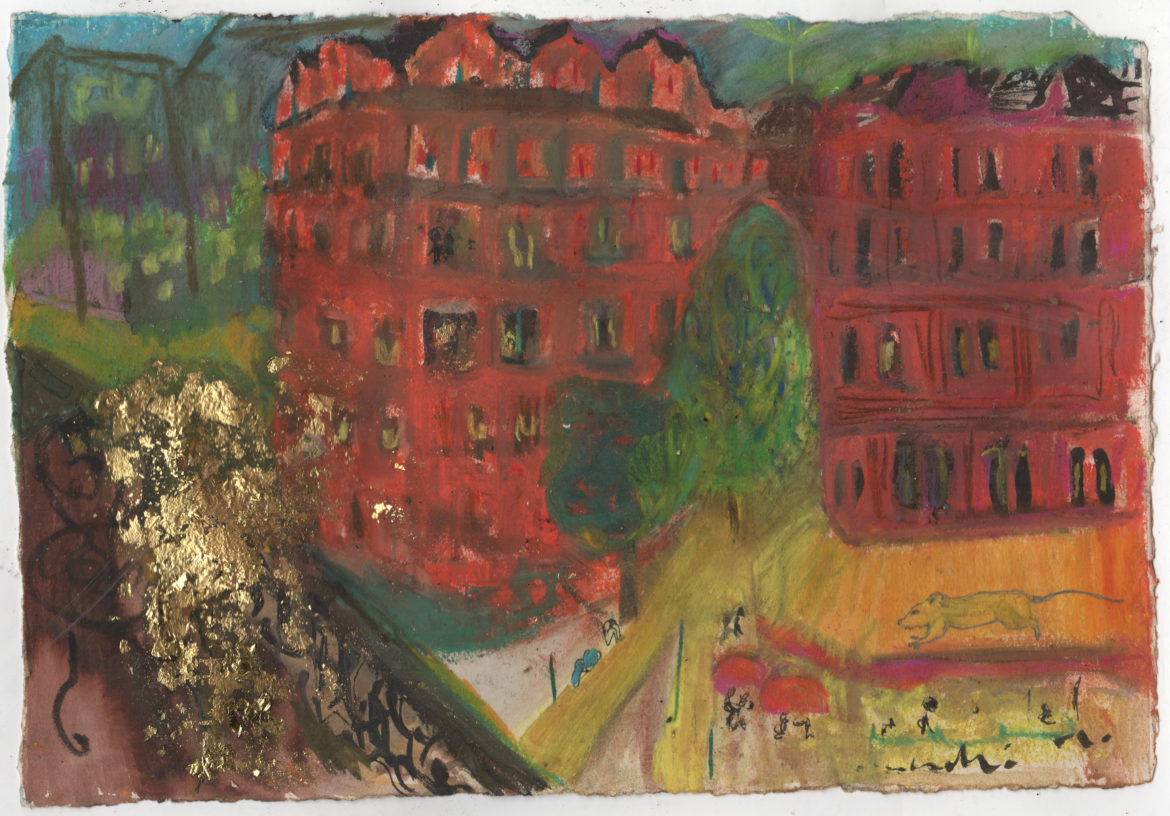

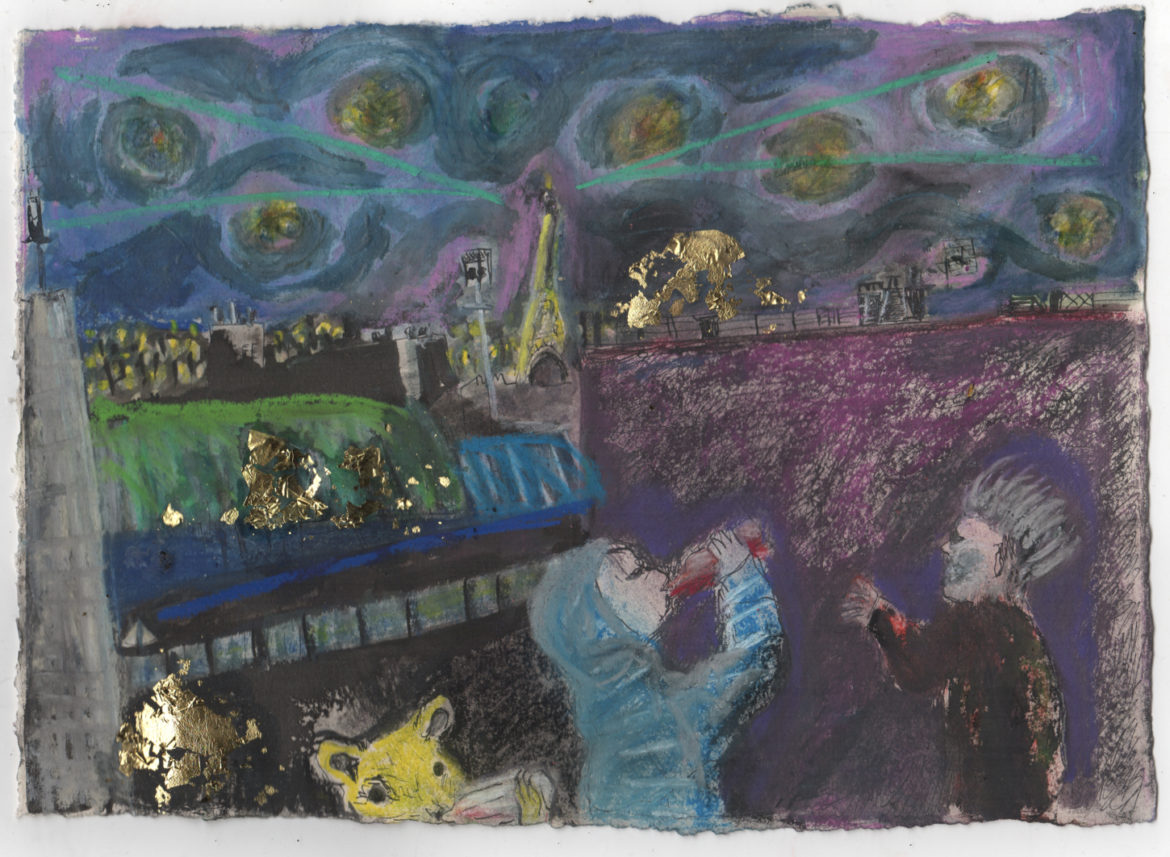

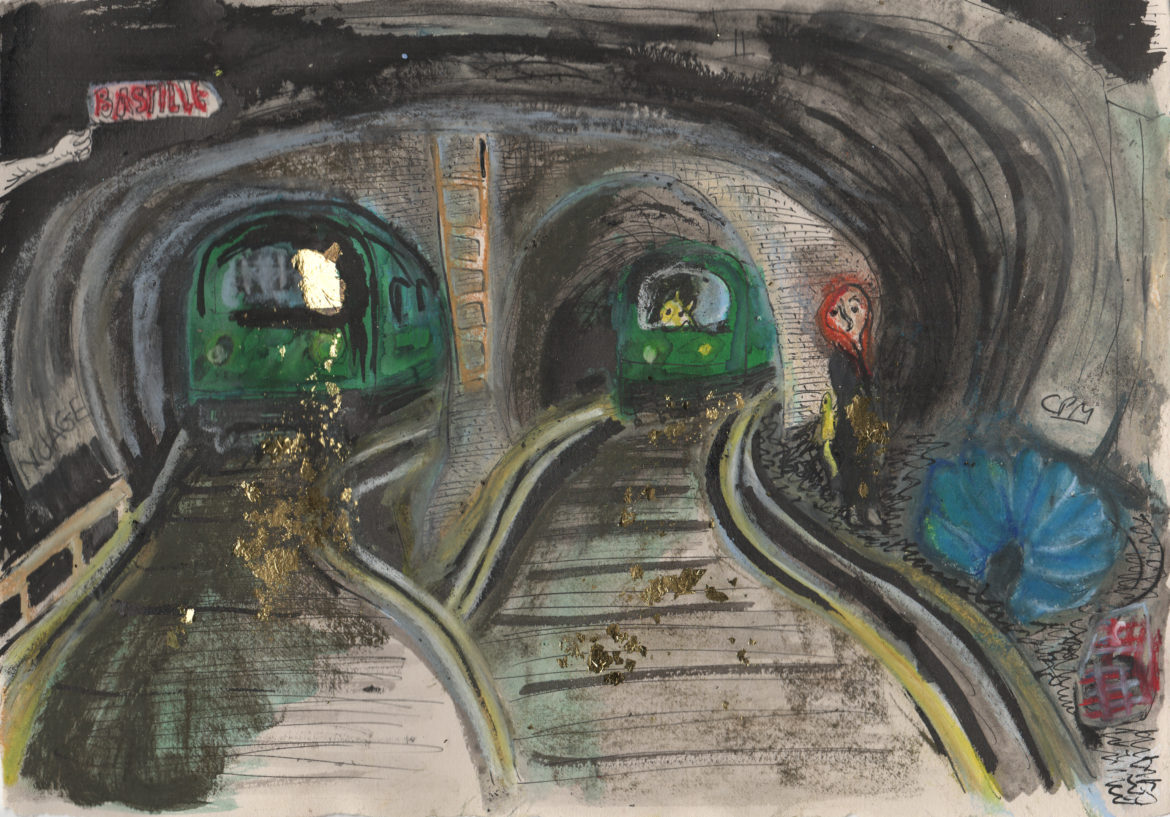

KT: Your work — as a visual artist, in any case — has been less fantastical/mystical than realistic though I have only been intimately familiar with the recent ones Paris Pavements where rodents play a very outsized role and the portraits of London through the faces and restlessness of dogs. Are there other works of yours in which myths and fantasy play a bigger role? I assume that using animals to tell a story is also a type of rebellion to more straightforward narratives.

JCM: I am just fascinated with animals. I love to watch them and draw them. It’s as simple as that.

Or is it? I am always returning to animals, different animals and I don’t know why. Not only in visual work but in other areas. I did a series of sonnets about my father as different animals. In this one, he is a pony.

Pony

They’re watching you, in their ungainly group,

pawing the ground, the great wet snorts

grunting the mountain air.

They’ve got their eyes right on you

and your lunch bag.

There’s always one, that fancies himself.

Not vain, not aware how pretty he looks,

but know he’s the one who’ll make a dash

for your cheese the moment you turn away.

I would retreat backwards, keeping your eyes forward.

Don’t slip. The ponies are interested now

and will take advantage of any show of fear.

Drop your guard and your contents

will be flying for the sierra, rustled.

KT: What are you usually trying to explore in your work? And are there convergences between your devotion to visual art as a storytelling medium and your work as a poet? Are there themes you see coming back to you whether you intend to or not?

JCM: Of course. What you are exploring is often only evident after the act of creation and you are approaching the work as a partial outsider, with the perspective of a viewer or reader. I see that animals are a subject matter and a means of exploring psychology. In the poem for my father, the Scottish folk ideas of witch-transformation from human to animal have found their way in, but I have not made this a feature of the poems. The sonnet simply shows my father as an animal, whereas I am still a human in the poem. He may already be a horse, in some way, as he is no longer alive.

KT: This is fascinating.

JCM: I think I am a great watcher of people and animals, and then in representing what I see back to the world cannot avoid drawing on the sardonic sense of humour that I have acquired from my father.

In your poetry I have recognised the theme of place and the encounter material and personal fragments of memory. Could you expand on this and any possible relation to Yorùbá culture? I was much taken by an insightful comment made on Edwardsville by Heart by the writer Chris Abani who wrote that ‘As in all Yorùbá ritual, it is the journey that holds it together.’ And could I ask more generally, what themes do you see in your work as either pivotal or unavoidable as a writer?

KT: I was also enamoured by that comment, especially because I had not set out, explicitly, to put my Yorùbá self in the work. I just wanted to document a time in poetry. I mean, it was inevitable in some way, since the work is about a time one year of which I taught Yorùbá in the University. And other elements of my language advocacy show up by default. Tonemarking the Yorùbá characters, for instance. But most of the other elements that showcase an obsession with language wasn’t planned ahead, so when Abani mentioned that, I was intrigued. The writer, Abani, though of Igbo extraction, has taken to Ifá, Yorùbá traditional knowledge and divination system, so it wasn’t much of a surprise. The journey is an important element of Yorùbá mythology. But as you said, there are some things we notice in our work only after its completion. The writer only starts the book. The reader completes it. I’m also interested in animals, as you saw in “Campus Deer”. I’m currently working on a biography of Wole Sóyínká from the angle of the Nigerian megafauna.

You mentioned Bernard Shaw earlier as one of your father’s influences. He was also one of mine. One of the reasons I wrote a long preface to my collection of poems is a homage to his style. It is to Peter King’s credit that he never gave me any problems about it. Most of Shaw’s plays always had one and I enjoyed reading them as a way to better understand his worldview or to interrogate one polemical issue he was addressing the play to. I want to see if I can bring back the preface as something to look forward to in a piece of writing.

JCM: Oh gosh, I had a complete book, a huge book, from my father of Bernard Shaw’s prefaces and essays. So much wisdom and wit.

KT: I agree!

JCM: It was enormous. But I don’t know where that’s gone now, perhaps it will turn up when I move house next year. I’m off to Hastings on the South Coast of England a new adventure. I’m hoping that the sea will start to turn up in my work then with all its rich metaphorical and storytelling power. As your book travels oceans I caught a salty whiff despite its inland location.

We mostly travel by air today, and I presume you yourself reached Edwardsville by plane, but ocean journeys, including the forced traffic of peoples on ships, fill my imagination when I think of international relationships and how they’ve developed in violence, colonisation and adventure. I was warmed by the generosity in which you talked about encountering relics of the history of slavery and civil war in your American hometown. I understand that your family were not personally slaves but we’re all, to say the least, touched by tales of slavery and that abuse of Africa by European America and other white communities haunts the modern world and leaves its physical legacy in many buildings and spaces.

KT: You’re right. There are a number of other connections I didn’t explore in this work that I have carried with me. For instance, the internecine Yorùbá wars ended at about 1883 or so when a final truce was signed between the warring kingdoms that had been fighting each other for about fifteen precious years. My great grandfather, Ogúngbola, was a young boy at this time. Our family legend has it that his father, who worked as a metal craftsman, or smith, for the military, having lived through the war, refused to enjoy the peace in that same environment where he had grown up. He took his son and walked to Ibadan, which was many hundred kilometres away. I don’t know how many weeks the journey took. But I am content, sometimes, to imagine it, and recreate the journey in my mind. I’m a native of Ibadan today because of that trip.

JCM: Sometimes it leaps out of us where we don’t expect, such as the craft market in Greenwich in London which I believe was once a place where people were bought and sold. It’s not so long ago. Who are we really? Is this anything to do with us these days? I don’t want to ignore its presence and pretend that there is no evil in our past. The devil is not Èṣù it is human. In this narrative of he has a white face. But we need to look at ourselves and poetry is good at this, helping us see ourselves, a kind of mirror.

KT: There is a place on Lagos Island —actually quite likely a number of places — where humans were sold off to the slave ships during those times. One of the things that bother me today, and which I’ve explored in other pieces of writing (journalism etc) in Nigeria is the disrespect for the value of memory that has ensured that we no longer remember where those places are. No monuments, no physical structures tell us these histories as a way of keeping visible the markings of what we used to be, and what we should never return to. There are a few slavery museums in the city today but they are poorly managed and don’t tell a good story, taking adequate responsibility.

JCM: I agree I want to be educated about history in place. I also feel that the landscape should not necessarily remember all our human stories of evil. I don’t want commemorative sculpture, for example, in all our forests and mountains. For me, that’s too human-centric and we’re doing enough to enslave the planet, all the animals, trees and rock, even. But I want to remember on buildings, in urban spaces, I don’t want it whitewashed away, or hidden as people understandably try to develop that desirable, assertive, self-confident national spirit in Africa. We need strong, healthy museums of slavery and genocide that don’t just fill us with embarrassment as well as shame. And I want to know the stories of buildings and their past so I can feel what has happened as I go around in the world with my eyes, at least partially, open.

Do you have any hopes for the effect of your book on its readers and the world? Any ideas what it can or might do? Or do you send it out with a ‘go litel bok’ as Chaucer said of his long poem Troilus and Criseyde? Your book will do what it will do and whatever happens, will be up to the text and its readers.

KT: I have sometimes thought about it, and then promptly discarded the question. The process of creating the book, and the number of tangents its tentacles touched, has convinced me that it will meet different people at different points of their mental or creative need, and that is fine. I’ve also sprinkled a lot of personal details around the work many of which will not be unravelled so soon because each human contact documented there happened, usually, independent of the other. Each part of the book will reveal itself differently, depending on how the reader has encountered me, or on their knowledge of my past and/or future work, or on the particular relevance of that part of the work to their present circumstance. As a memoir, it is my selfish diary to interrogate the world through a series of contacts. But each human story is also universal, so I will hope that this value of the work endures, both as an extension of my own limited adventures, and on the merits of the work’s attempted ambitions: a poetic vessel for travel stories. In other words, to answer your question better, if I have hidden any notable fuses in-between the lines of the poems, I don’t want to personally determine when they detonate, if they do at all. I’m content to have it either as a benign enjoyable art or as a provocative political statement.

JCM: I would love to read your author prefaces and would like to see more informative and reflective author prefaces generally. Often what we see in their place is a professional endorsement by a writer chosen to give authority to a work, some of which merely offer encouragement to both reader and writer. For my first collection of poems, For the Messengers (Donut Press, 2011), I wrote an extensive preface about archiving Reuters Television News as the poems were about working with international footage during 2008. It felt crucial to give some insight into my world of work, explain how writing poetry helped stop me from becoming desensitised to the violence I was witnessing daily on screen in a time before images of conflict became so much more easily available on the internet. What did I need to communicate that? A writer’s preface!

KT: It’s a lost art, I think, the preface. I’m very happy to reclaim that space for my own voice, in prose, for the benefit of the reader never too impatient to rush into the book. Glad to know that I’m not alone!

Before this conversation ends, I would like to ask about your collection titled The Wires (2012) not about what influenced it, ‘cos you explained that already in the preface, it is about the process. How do you decide that a book is ready to go to press? How do you know a poem is ready to be seen by a third party? If you’re like me, you second guess yourself and keep nibbling at the lines day in day out trying to find the perfect rhythm. Peter J. king says “poetry is never completed. It’s simply set aside.” I think he said he was quoting someone else. How do you decide you’ve reached the “setting aside” point?

JCM: Ah, that point. It’s magic. Who knows? It’s different for everyone. I think the answer is not only about the work but about yourself. When are you ready to move on? Really ready? Then I think you must stand aside and not return to it for a period of time – even if that space you give yourself is only weeks, two weeks if you must, but a certain distance. This gives you a perspective on the work which helps you judge it from the outside. When you return you mustn’t jump in and rewrite. Instead, ask yourself, is this complete for me? Does this feel ripe? That’s my general rule to myself. I wish I took my own advice more often. Basically, I’m saying, use the different parts of yourself to judge your own work, you have multiple viewpoints inside yourself. And when I judge my own work, as well as using my editing skills I use my emotion. Feeling is the touchstone of poetry. Wordsworth’s chestnut was that poetry was ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’. I’d like to turn that upside down for this stage of the process and talk of emotion recognised in tranquillity. It’s not as well realised as Wordsworth’s philosophical aphorism but I’m scratching for something I have never expressed before.

Conversely, you can show your poetry to an editor-poet who is a very good judge of poems, like Peter J. King. ὅπερ ἔδει ποιῆσαι.

KT: He’s very good, I agree. He let the work breathe without too much of an intervention. Looking at what worked and what didn’t through his eyes was very helpful in judging the success of my experiments. What was that Greek-looking expression you wrote at the end there?

JCM: As Peter’s partner, Andrea is Greek, he has a passion and knowledge for the Greek language. That is a version of QED, not quite the same but more apt here. I meant it to say, in a roundabout way, that as Peter has worked on both of our recent collections, he has helped us decide when we’re ready for print. Oh, the value of a good editor and friend!

KT: This has been a wonderful conversation.

JCM: Hasn’t it! Thank you very much.